.270

The Weiser River, dammed and slow, idles southward, and hills dotted with sage roll into its west bank. The eastern bank flattens to a valley that runs north until the river bends back on itself, and as if the shape of the bend reflected on the landscape, the bank sweeps upward into a network of canyons. The Bureau of Land Management owns the ground where I'm sitting, but my Father-in-Law owns the ground I'm looking at. Before him missionaries had it, and halfway down the ridge to the river stands a wooden cross large enough to crucify a man on. Last year I killed a spike elk on the other side of the cross in a drainage with a spring. I've eaten all the meat and I need another.

It's eight-thirty in the morning. Sunlight just painted the tips of the south-facing slopes. Through my binoculars I see a small elk herd walk into the sunlight. Eight cows and three calves. Three hundred yards away. No bulls. I continue to watch them move, not so slowly, up to the higher and deeper expanse of desert. Then gone over the top.

My attention turns to the valley, and I wonder what's happening at the ranch house, far to the south and out of sight. My Father-in-Law raises cattle in the valley and I help butcher at least two heifers a year. He imagines two lines connecting their ear to the opposite eye, forming and "X" on their forehead, and shoots them in the middle of the "X" with a .223 Remington Model 700. They die instantly. We skin, gut, and quarter the carcass into four large sections and hang them in his refrigerated butchers room for two weeks, then cut and package the meat. Everyone in my family participates in the process. My four year old daughter tears off pieces of tape to hold the packaging together, much like, I imagine, my wife did at her age.

Alone, without any wildlife to admire now, I pass the time by eating a ham sandwich. I'm trying to resist the urge to change positions. I practice a few dry-fires at rocks across the canyon. Drink some water. Get behind those binoculars. Study the land. My mind drifts to my own father and how he would like to see all of this. I went to college as a disguise to hunt the west, and he knew it, and let me go anyway. I stayed. He bought me an engraved Browning BAR .30-06 when I turned fourteen. I sold it for a bolt-action .270 Winchester. It seemed more western, more Jack O'Connor. More me.

My reflections halt as I look to the western hills. A herd of one hundred or more elk emerge out of the river into the valley. I can see water dripping off them through my binoculars. They're headed to the backside of the cross. I have to hurry to intercept them. I pack up my binoculars and tripod, chamber a round into my rifle and sling it over my shoulder. Making my way down I almost stubble over a rock covered with grass, then cross some sage flat, and climb up to a saddle on the neighboring ridge. Now I'm breathing too hard. They're just on the other side. I didn't really think this over. I should have come in from above them, with the wind in my face and waited in the sage for them to bed down. I get on my belly and crawl. I see a point of a bull's antler, his body hidden by the crest of the ridge. A cow elk walks in front of him, sees me, and runs. The entire herd follows. The stampede sounds like a thousand rocks falling. They circle back to where the ridge meets the valley bottom and run south across the valley, a cloud of dust trailing them. As I lay on my belly I watch them head up into the canyon that lays behind where I had come from. I open the action of my rifle and remove the cartridge, placing it back in the magazine.

The box-canyon the elk went into forms a wall-like fortress on the eastern side and to get above them, up-wind, I'll have to climb to the very top of the plateau. That means pain. But I think about not going, and the pain of disappointment creeps in, and I let it encompass me for a moment to motivate me to stand. I get to one knee, then to both feet. Looking at the top I sling my rifle and step forward, uphill.

The wind feels slight and fresh against the sweat on the back of my neck. As I reach my previous vantage, where I had sat with my binoculars, I sneak around a rock out-cropping, trying to gain a view into the canyon behind. A small dry rock bed created by run-off cuts down the slope. In its recess I sit down, the sage-brush hiding me. I setup my binoculars once more. It doesn't take long to find them. The north-facing slope unites with the wall of the box-canyon and the elk have bed down on a bench where the two meet. If I stand and walk they will see me.

I sheath my rifle in my pack and facing downhill, begin to crawl like a bear down the dry runoff shoot. I lose my wrist-watch somewhere along the way. My pack keeps wanting to come over my shoulders, so I start crawling sideways. Sweat drips onto the back of my hands. I stop to rest. The fragrance of sage and dust and salt surround me. The sun shines fully on the barren terrain. I wonder what Marcus Luttrell, who dragged his broken body up and down Afghanistan, would say to me right now, and not wanting to find out I crawl again.

As I reach the bottom a Hungarian partridge scampers off but does not take flight. I look up and examine the landscape I will suffer over, then back at the elk, still bedded. Slithering between rocks and sagebrush, I crawl uphill until I cross the crest of the ridge, and then a bit more until I'm on the lee-side. Now I can stand. From here, the slope steepens, the terrain grows more rocky, and my legs burn like kerosene as I hike to the top of the plateau. A minute no longer equals a minute. The slower I move my legs the slower time moves his hands. Near the top I intercept a dirt road. I feel guilty somewhat that the hardest climbing is over. At the top now, I ready myself to kill, and begin working down the canyon where the elk lay.

I chamber a round into my rifle, pick around a boulder, and study what I see. The elk lay spread out on the canyon floor and up the north side. Nothing much to hide them except the canyon-walls. All I see are cows. I take my pack off and slide slowly on my bottom until I reach the next rock that will hide me. Now I can see them all, and what feels like looking straight down a bull sleeps with his back toward me. I'm looking at his spine between his shoulder blades. He's turned enough that if I shoot him to the left of the spine the bullet would come out his right brisket. Its a small window, but I know I can do it. Two-hundred yards. I set my rifle across the rock in front of me. The angle's not right. I scoot down again and find another rock. They have no idea I'm here. The bull feels close in my scope and I switch my safety off and put my finger on the trigger. I hold the cross-hairs just to the left of the spine. I breath deep and exhale. A sliver of doubt creeps into my mind. I don't let anything move except my trigger finger, slowly pressing. The shot surprises me but I don't hear it. Through the scope as the rifle recoils I can see the bull drop his head. The entire herd moves like a flock of geese pushed off a field. Except the bull. I know I shot perfect and I think he's dead. But he gets up, so slowly. I rack another round into the chamber. He's standing broadside now. He takes one step. I shoot again and he falls, legs in the air.

Time does strange things after you do something like that. The time around you slows down, but the time inside you speeds up. In the time it takes me to inhale and switch my safety on, I analyze my fears and doubts concerning my abilities and weigh them against my successes, and come to the conclusion that I'm essentially a more skilled and thorough version of my twelve year-old self. I know the elk is dead and feel sorrow for killing him, but glad that I did it well. The land seems to stretch out beyond the horizon as one connected place, and all of the sudden my past and my future seem connected as well, like I am looking at a map and I am in the middle of it, and everything to the south happened yesterday and everything to the north is yet to come, and I can see the terrain of my life clearly for the first time, the sun shining on it all.

I hike down to him and quickly begin butchering. I gut him, skin his left side, remove his hind quarter, front quarter, back-straps, the slabs of meat from his flank, brisket, and then cut out the meat between his ribs. I'm beginning to turn an animal into meat. I put the meat in game-bags resembling cheese-cloth, then flip him over and go through the same sequence on the other side, this time removing all the neck meat as well. Flies start to gather. I have to shoo them away with an extra shirt every twenty or thirty seconds. I run out of water and my legs spasm softly if I let them rest. I want to hike the meat out on my back, and have an internal battle with my ego. I'm afraid to leave the meat unattended with the flies as I shuttle the loads back and forth. My cell phone surprisingly has service. It feels foreign and sinful in my hands out here. I call my wife at the ranch house. She, my Father-In-Law, and two of his friends drive out, using the dirt road I hiked on. They can't find me, and spend the better part of an hour looking. I shoo flies and think about how I should have just starting hiking loads out to my truck. Dusk begins. I'm still thirsty.

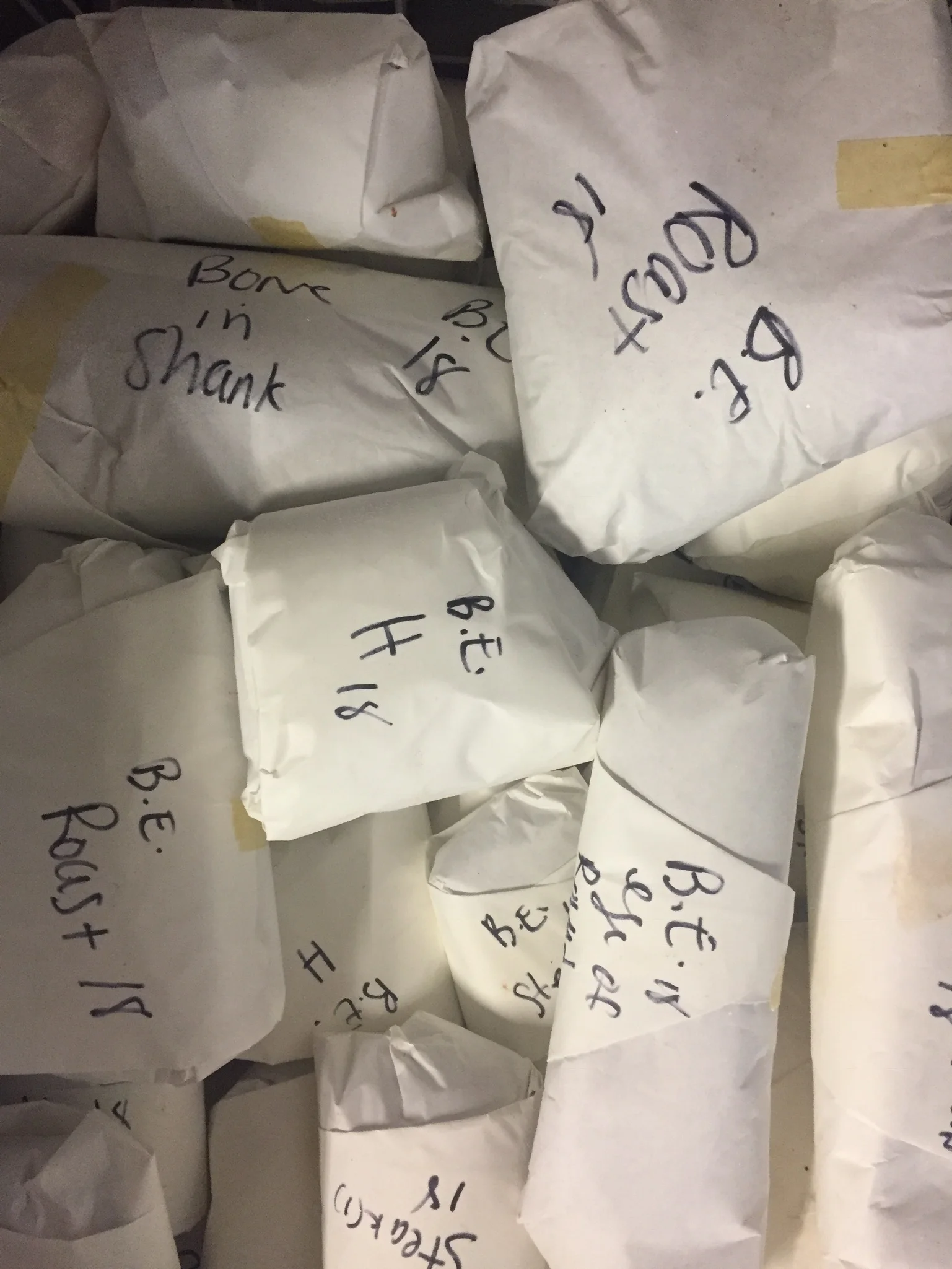

The meat is divided between four bags by the time we find each other. We each haul a bag on our shoulders to where my Father-in-Law parked. I sever the bull's head from his spine and pack that out too. Driving over the country as the sun sets, it feels strange to cover ground so quickly. The valley seems smaller as I'm carried along, and the canyons not so high, and it’s hard to reconcile how my body feels with how quickly the machine traverses the country, and though I'm glad to be headed down, I wish I had hiked it out myself. We drive to my pickup truck, where I parked that morning in the valley. I drive it to the ranch house. We hang the meat in the butcher's room where my Father-in-Law processes beef.

I head inside the ranch house to find a glass of water. I want to rest, but instead I clean my rifle in the basement. As I run the cleaning rod through the barrel I think about how long it took me to finally arrive at a place where my reality and dreams felt the same, and I'm reminded that God sent Joseph into slavery and prison before he met Pharaoh. I think about how I used to hunt with my Father in Michigan, and now we both hunt alone, and he's getting older, and I guess I am too. I wipe down and oil the outside of my rifle. I wonder what the rest of my life will be like, and I think I know, and wonder how long it will last, and how much of it will feel like climbing, and how much of it will feel like falling. I put my rifle back in its case. I feel alive like I never have before, like every minute brought me here, and I'm headed to the edge of my map, and even if I get lost I've got a compass inside me that brought me here, and it will lead me on into the unknown.

Next weekend we'll come back to cut and package the meat. A job and a weekly routine wait for me in Boise. My wife and I load up my truck, buckle our two children into their car-seats, and say goodbye to her parents. I picture the city-lights of Boise against the night sky, seen from a distance, and a hollow dread shadows me as I anticipate merging with civilization again. I think of where I started the hunt, at the cross, and I'm reminded that even Jesus, when he went to the mountains to pray and be alone, returned to commune with Judas. I drive the truck to the end of the driveway, turn right onto the dirt road that follows the river, and head south out of the valley, the canyons behind me.